|

Social Role Valorization

|

|

Overview

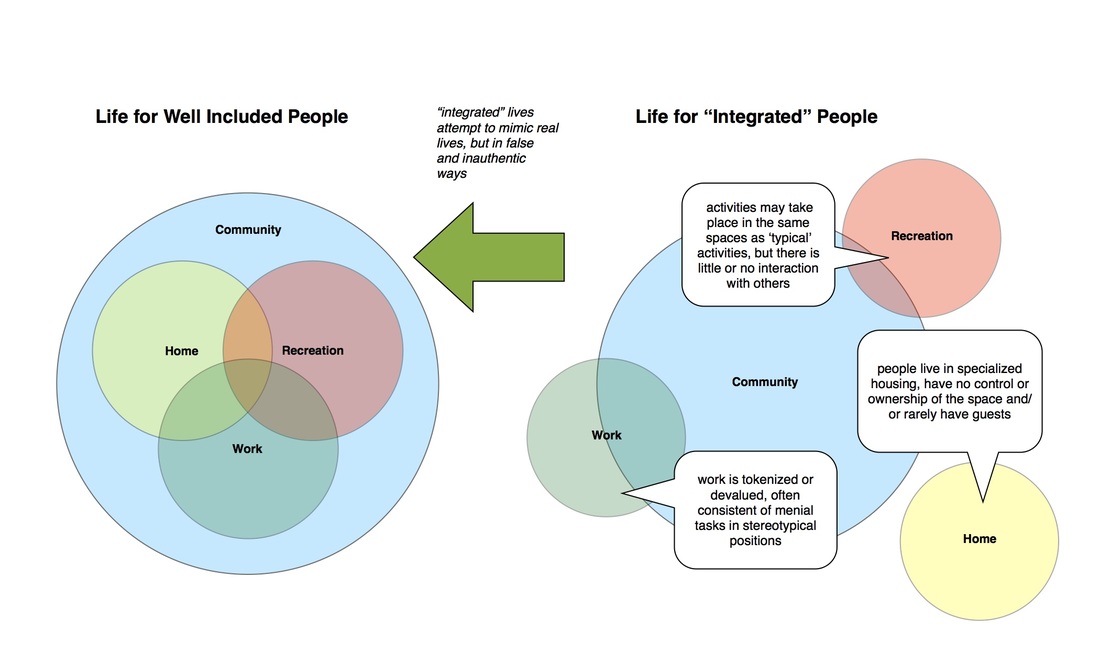

Social Role Valorization theory began as a way to figure out how to support people on the margins to participate in socially valued activities. The idea is that when people hold valued roles, they are more likely to receive the opportunities that will help them to achieve 'the good life' that goes along with those roles. This philosophy is very deeply embedded in the development of Inclusive Post-Secondary Education. The theory also recognizes that many of the wounding experiences of exclusion result in behaviours that are frequently interpreted as 'symptoms' of developmental disability. When we are supporting people we often have to stop and recognize that the student is struggling with one of these experiences and sometimes we have to temporarily shift our support in ways that are uncomfortable and inconvenient for us in order to help have experiences that make them feel valued members of the post-secondary community. Common Wounds of Devalued People Rejection: Rejection by family, peers, and groups can stem from the idea that people with intellectual and developmental disabilities should be 'with their own kind.' It can be experienced as physical or social segregation. The outcome of repeated rejection is that students, in turn, may reject society. They may not want to behave in ways that give them a positive self image because they don't see a point in trying to fit in only to be rejected again. They may withdraw, not care about their appearance or hygiene and act in ways that are 'deliberately' rude. Accorded low social status: When you notice the patterns of how people with intellectual and developmental disabilities are treated in society, this is pretty obvious. For example: the frequency with which the 'R' word is an acceptable term for insulting something, how frequently people who are labelled in high school are involved in recycling programs (ie picking up the garbage of normal people), the fact that special education classrooms are almost always in the basement, the tone of voice people use when addressing someone with an obvious label. Etc. Students are frequently very attune to these reactions from others and will react back either with anger or by withdrawing. Physical and social discontinuity: Because people with intellectual and developmental disabilities are often put into artificially constructed situations (for example volunteer and paid friends, segregated classrooms, specialized recreation activities) they often experience physical and relational discontinuity as their relationships and activities are defined by their roles as service recipients. This can cause strange ways of interacting with others that make people who have been well-included confused or uncomfortable. The most common example of the reaction of students to this experience is by attaching themselves to people in ways that are often perceived as 'clingy.' However, if we step back and recognize students have never had genuine relationships, they also may have an expectation that things must revolve around them, and are unsure of how to negotiate friendships. Usually, our role is about supporting the potential friend to understand this history and feel comfortable about having a natural relationship with a friend including setting boundaries and being authentic about who they are. We can then support the student to learn how to navigate the ups and downs of natural reciprocal friendships. De-individualisation: Through interacting with large, bureaucratic structures, people with intellectual and developmental disabilities often experience a loss of 'positive identity': low self-esteem, little belief in their future and feeling out of control of their own life. Our solution is to support students to adhere to the most typical path possible at University or College, including participating in things based on their interest (e.g. clubs and course unions). We also commonly see this when students perceive their whole identity to being about being a person with a disability. Although being an advocate for people with disabilities is a generally positive role in society, it also negates the idea that they have anything else to offer or be interested in. Loss. People with intellectual and developmental disabilities lose control over their life, even small choices that might seem on the surface to be unimportant become significant. The realization that a student has control over their experience at post-secondary can take a long time to sink in for them. It often looks like students being very submissive ("can I go make a phone call?") ("is it okay if I go to class late?") or power tripping on staff over little things ("I will not do that just because you said so"). Often times this last one is a good moment to check in and ask yourself 'is this really important? why am I trying to control this? did I explain it in a way that this person understands the consequences of not doing this?' and remind yourself - your job is to support the student through the decision process (including the fallout), not to support them to make the "right" decision! Deprivation. When people are segregated, they are deprived of normal life experiences (like making mistakes, for example). This means means that when they are in the 'real world' they do not have the same context for social expectations. This most commonly becomes obvious students have been segregated into a "special" education classroom in high school. When they join a regular University or College classroom, they are missing all those unwritten rules about how to be a student in a classroom, such as raising your hand or greeting (or not greeting) fellow students. Normalization SRV began as the theory of normalization. The theory assumes that people are more likely to be integrated into community when they are part of the normal rhythms of daily life. These daily routines are not experienced by people who participate in segregated options. These rhythms are flexible and authentic, not part of an attempt to replicate 'real life' in a false way based on labels. "Human services usually address the same human needs that all people have such as physical care, a place to live, and opportunities for growth and development, health care, and education. However, the manner in which many disability services address these needs is very different from the ways in which ordinary valued people have these needs met. The normalisation principle of the ‘culturally valued analogue’ stated that services should be modelled as much as possible on culturally valued ways of addressing the particular needs concerned.” source This diagram examines some of the ways that replication of ‘services’ for people with developmental disabilities does not lead to inclusion in community.

Normal Rhythms

The following examples of normal rhythms focus on life generally, as facilitators we also look at the normal rhythms of campus life for students who are getting the most out of their experience. We also consider the ways in which the needs of students are met generally and supporting students to take advantage of these generic student services rather than relying entirely on facilitators. Normal Rhythm of the Day: Anticipate the upcoming events of the day, have a reason to leave the house, have significant parts of the day that are not completely prescribed and monotonous, participate in events [meals, other activities] when it is normal not when it is convenient for staff, have accomplishments to reflect on at the end of the day. Normal Rhythm of the Week: live in one place that is different from where you work and hang out during the day, anticipate leisure activities at the weekend, look forward to school or work on Monday Normal Rhythm of Life: experience normal rhythms of holidays and seasonal activities, participate in normal markers of growth and change, have a wide range of choices, wishes, and desires that are considered and respected, have normal economic standards, live in a normal house in a normal neighbourhood. Think About:

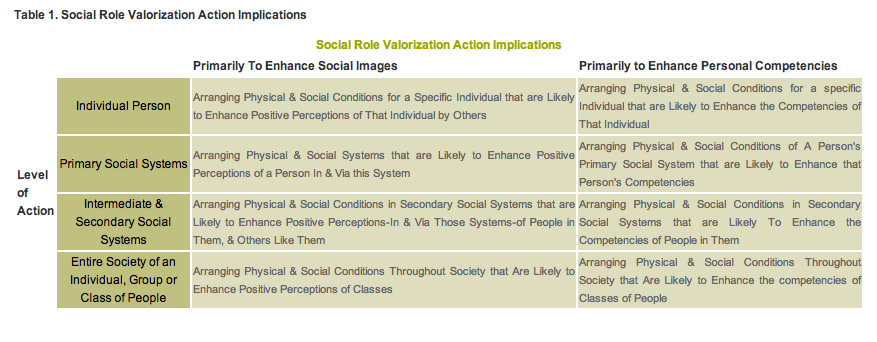

Philosophy of Social Role Valorization There are two main ways to achieve role-valorization for devalued people:

A simple way of thinking about this is "disrupting the self-fulfilling prophecy." These two ideas go together and reinforce each other in ways that are both positive and negative. For example, people with intellectual and developmental disabilities who are involved in things that devalue their image (participating in socially devalued or childlike activities; dressing in ill-fitting, seriously dated/unflattering or worn clothing; always being seen in a group of people with disabilities or with a support person) are significantly at risk of people having low expectations of their competency ('let me do that for you' 'he/she could never do that!' etc). The reverse is also true - people who demonstrate low competency will have a devalued image in society. In contrast, when someone demonstrates a positive social image (independence and confidence, professional and age-appropriate clothing, participating in the mainstream, niche activities) he or she is more likely to be provided with opportunities to have experiences that expand his or her competencies. This also means that when someone with an intellectual and developmental disability demonstrates their competency, their social image is seen in a positive way. It is important to think about the fact that this happens both on the individual level, all the way up to being a part of the pattern of society. This chart looks at how these two factors play out on micro (individual) and macro (structural/societal) levels. Source: socialrolevalorization.com Action Implications for SRV

Source: socialrolevalorization.com

SRV has a role in protecting people who are devalued in society from experiencing the harm that is associated with being on the margins. When your life is valued, people are more likely to hear your voice when something is wrong. Others are also more likely to stand up for you, and notice when you are not there.

In order to value people on the margins, non-marginalized people need to feel connected to the marginalized individual and to recognize the similarities between themselves and that person. This is different than the charitable way that we typically see people when they express empathy (pity) by raising money for things that perpetuate their segregation (otherness from themselves). Often we find our role as facilitators is to model for others that we value this person and to help the students we work for demonstrate that they are leading valued lives. SRV is a powerful paradigm shift for thinking about disability in the world. Most people are not aware that they could think differently about people with intellectual and developmental disabilities; people are embedded within the traditional human service model that says people need to be protected and require something special and different. Many people can be very resistant and feel threatened when you challenge this mindset, even in gentle ways. This is especially important to be aware of we are interacting with service providers who offer segregated, non-coherent services in the community. This may also be (more) true when requesting courses or employment within fields that see themselves as having specialist knowledge about people with labels. We always strive to let the evidence speak for itself, and not argue or defend the value of inclusion. Other strategies for having these tough interactions are discussed in more detail in the facilitation tools section. Think About:

Summary SRV is a large theory and requires a significant commitment to study and practice in order to fully master. This page provides a very brief introduction. It is important to state here that the goal of Inclusive Post-secondary Education is not to normalize students but to make their participation in post-secondary education the norm. Next: Facilitation Tools

|